Chapter 12 Guided Reading Answers Georgia and the American Experience

Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze, Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way, 1862. Mural, United states of america Capitol.

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Delight click hither to improve this chapter.*

- I. Introduction

- Two. Antebellum Western Migration and Indian Removal

- III. Life and Culture in the West

- IV. Texas, Mexico and the United states

- 5. Manifest Destiny and the Gold Rush

- VI. The Monroe Doctrine and Manifest Destiny.

- VII. Conclusion

- Eight. Master Sources

- Nine. Reference Material

I. Introduction

John Louis O'Sullivan, a pop editor and columnist, articulated the long-standing American belief in the God-given mission of the United states to lead the earth in the peaceful transition to republic. In a little-read essay printed in The United States Magazine and Democratic Review, O'Sullivan outlined the importance of annexing Texas to the United States:

Why, were other reasoning wanting, in favor of at present elevating this question of the reception of Texas into the Wedlock, out of the lower region of our by political party dissensions, up to its proper level of a high and broad nationality, it surely is to be constitute, found abundantly, in the style in which other nations accept undertaken to intrude themselves into it, between us and the proper parties to the case, in a spirit of hostile interference against united states of america, for the avowed object of disappointment our policy and hampering our ability, limiting our greatness and checking the fulfillment of our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.1

O'Sullivan and many others viewed expansion as necessary to achieve America's destiny and to protect American interests. The quasi-religious call to spread democracy coupled with the reality of thousands of settlers pressing w. Manifest destiny was grounded in the belief that a democratic, agrestal republic would salvage the world.

John O'Sullivan, shown hither in a 1874 Harper's Weekly sketch, coined the phrase "manifest destiny" in an 1845 newspaper article. Wikimedia.

Although called into name in 1845, manifest destiny was a widely held just vaguely defined belief that dated back to the founding of the nation. Kickoff, many Americans believed that the strength of American values and institutions justified moral claims to hemispheric leadership. Second, the lands on the Due north American continent westward of the Mississippi River (and later into the Caribbean) were destined for American-led political and agricultural improvement. Tertiary, God and the Constitution ordained an irrepressible destiny to achieve redemption and democratization throughout the world. All three of these claims pushed many Americans, whether they uttered the words manifest destiny or not, to actively seek the expansion of republic. These behavior and the resulting actions were oft disastrous to anyone in the way of American expansion. The new religion of American democracy spread on the feet and in the wagons of those who moved west, imbued with the hope that their success would exist the nation'due south success.

The Young America movement, strongest among members of the Democratic Party merely spanning the political spectrum, downplayed divisions over slavery and ethnicity by embracing national unity and emphasizing American exceptionalism, territorial expansion, democratic participation, and economic interdependence.ii Poet Ralph Waldo Emerson captured the political outlook of this new generation in a speech he delivered in 1844 titled "The Immature American":

In every age of the world, there has been a leading nation, one of a more generous sentiment, whose eminent citizens were willing to correspond the interests of general justice and humanity, at the risk of being chosen, by the men of the moment, chimerical and fantastic. Which should be that nation simply these States? Which should pb that movement, if not New England? Who should lead the leaders, but the Immature American?3

However, many Americans, including Emerson, disapproved of aggressive expansion. For opponents of manifest destiny, the lofty rhetoric of the Immature Americans was nil other than a kind of imperialism that the American Revolution was supposed to take repudiated.4 Many members of the Whig Party (and later the Republican Party) argued that the United States' mission was to lead by instance, not past conquest. Abraham Lincoln summed upwardly this criticism with a fair amount of sarcasm during a speech communication in 1859:

He (the Immature American) owns a large part of the world, by correct of possessing it; and all the balance by right of wanting information technology, and intending to take it. . . . Young America had "a pleasing promise—a fond desire—a longing after" territory. He has a peachy passion—a perfect rage—for the "new"; peculiarly new men for office, and the new earth mentioned in the revelations, in which, being no more than bounding main, there must be most 3 times as much state as in the present. He is a great friend of humanity; and his desire for land is not selfish, but but an impulse to extend the area of freedom. He is very anxious to fight for the liberation of enslaved nations and colonies, provided, always, they take land. . . . As to those who have no land, and would be glad of help from any quarter, he considers they tin can afford to wait a few hundred years longer. In knowledge he is specially rich. He knows all that tin can possibly exist known; inclines to believe in spiritual trappings, and is the unquestioned inventor of "Manifest Destiny."5

But Lincoln and other anti-expansionists would struggle to win popular opinion. The nation, fueled past the principles of manifest destiny, would continue due west. Along the mode, Americans battled both native peoples and strange nations, claiming territory to the very edges of the continent. But west expansion did not come without a cost. It exacerbated the slavery question, pushed Americans toward civil war, and, ultimately, threatened the very mission of American commonwealth it was designed to aid.

Artistic propaganda like this promoted the national project of manifest destiny. Columbia, the female person figure of America, leads Americans into the Due west and into the hereafter by carrying the values of republicanism (as seen through her Roman garb) and progress (shown through the inclusion of technological innovations like the telegraph) and clearing native peoples and animals, seen being pushed into the darkness. John Gast, American Progress, 1872. Wikimedia.

II. Antebellum Western Migration and Indian Removal

After the War of 1812, Americans settled the Great Lakes region rapidly thank you in function to aggressive land sales by the federal regime.half-dozen Missouri's access as a slave country presented the first major crisis over w migration and American expansion in the antebellum period. Farther north, atomic number 82 and fe ore mining spurred development in Wisconsin.vii By the 1830s and 1840s, increasing numbers of German and Scandinavian immigrants joined easterners in settling the Upper Mississippi watershed.8 Niggling settlement occurred w of Missouri as migrants viewed the Great Plains as a bulwark to farming. Farther west, the Rocky Mountains loomed every bit undesirable to all but fur traders, and all Native Americans due west of the Mississippi appeared too powerful to allow for white expansion.

"Do non lounge in the cities!" commanded publisher Horace Greeley in 1841, "There is room and health in the state, away from the crowds of idlers and imbeciles. Go west, before you are fitted for no life merely that of the factory."9 The New York Tribune frequently argued that American exceptionalism required the United States to benevolently conquer the continent as the prime ways of spreading American capitalism and American republic. Yet, the vast West was not empty. Native Americans controlled much of the land due east of the Mississippi River and almost all of the West. Expansion hinged on a federal policy of Indian removal.

The harassment and dispossession of Native Americans—whether driven by official U.South. government policy or the deportment of individual Americans and their communities—depended on the conventionalities in manifest destiny. Of course, a fair bit of racism was part of the equation besides. The political and legal processes of expansion always hinged on the conventionalities that white Americans could all-time apply new lands and opportunities. This belief rested on the idea that merely Americans embodied the democratic ideals of yeoman agriculturalism extolled by Thomas Jefferson and expanded under Jacksonian republic.

Florida was an early test case for the Americanization of new lands. The territory held strategic value for the young nation's growing economical and military interests in the Caribbean. The most important factors that led to the annexation of Florida included anxieties over runaway enslaved people, Spanish fail of the region, and the desired defeat of Native American tribes who controlled large portions of lucrative farm territory.

During the early nineteenth century, Spain wanted to increase productivity in Florida and encouraged migration of mostly southern enslavers. By the second decade of the 1800s, Anglo settlers occupied plantations along the St. Johns River, from the border with Georgia to Lake George a hundred miles upstream. Kingdom of spain began to lose control as the area chop-chop became a oasis for slave smugglers bringing illicit homo cargo into the United States for lucrative sale to Georgia planters. Plantation owners grew apprehensive almost the growing numbers of enslaved laborers running to the swamps and Native American-controlled areas of Florida. American enslavers pressured the U.Southward. government to confront the Spanish authorities. Southern enslavers refused to quietly accept the continued presence of armed Black men in Florida. During the War of 1812, a ragtag assortment of Georgia enslavers joined by a plethora of armed opportunists raided Spanish and British-endemic plantations along the St. Johns River. These private citizens received U.S. government assistance on July 27, 1816, when U.S. ground forces regulars attacked the Negro Fort (established as an armed outpost during the war by the British and located about sixty miles south of the Georgia edge). The raid killed 270 of the fort'due south inhabitants every bit a result of a direct hitting on the fort's gunpowder stores. This conflict set the phase for General Andrew Jackson'south invasion of Florida in 1817 and the offset of the Commencement Seminole State of war.10

Americans also held that Creek and Seminole people, occupying the area from the Apalachicola River to the wet prairies and hammock islands of central Florida, were dangers in their ain right. These tribes, known to the Americans collectively as Seminoles, migrated into the region over the course of the eighteenth century and established settlements, tilled fields, and tended herds of cattle in the rich floodplains and grasslands that dominated the northern third of the Florida peninsula. Envious eyes looked upon these lands. After biting disharmonize that often pitted Americans against a collection of Native Americans and formerly enslaved people, Spain eventually agreed to transfer the territory to the U.s.. The resulting Adams-Onís Treaty exchanged Florida for $v million and other territorial concessions elsewhere.11

Later the buy, planters from the Carolinas, Georgia, and Virginia entered Florida. Yet, the influx of settlers into the Florida territory was temporarily halted in the mid-1830s by the outbreak of the Second Seminole State of war (1835–1842). Complimentary Blackness men and women and escaped enslaved laborers likewise occupied the Seminole district, a state of affairs that deeply troubled enslavers. Indeed, General Thomas Sidney Jesup, U.Due south. commander during the early stages of the Second Seminole War, labeled that disharmonize "a negro, non an Indian War," fearful as he was that if the revolt "was not speedily put downwardly, the Due south will feel the consequence of it on their slave population earlier the end of the adjacent season."12 Florida became a state in 1845 and white settlement expanded.

American activity in Florida seized Indigenous people's eastern lands, reduced lands available for liberty-seeking enslaved people, and killed entirely or removed Native American peoples farther west. This became the template for time to come action. Presidents, since at to the lowest degree Thomas Jefferson, had long discussed removal, merely President Andrew Jackson took the well-nigh dramatic activeness. Jackson believed, "It [speedy removal] volition place a dense and civilized population in big tracts of country now occupied past a few savage hunters."13 Desires to remove Native Americans from valuable farmland motivated land and federal governments to cease trying to assimilate Native Americans and instead program for forced removal.

Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, thereby granting the president dominance to begin treaty negotiations that would give Native Americans state in the Due west in exchange for their lands east of the Mississippi. Many advocates of removal, including President Jackson, paternalistically claimed that it would protect Native American communities from exterior influences that jeopardized their chances of becoming "civilized" farmers. Jackson emphasized this paternalism—the belief that the authorities was interim in the all-time involvement of Native peoples—in his 1830 State of the Wedlock Address. "It [removal] will split the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites . . . and perhaps cause them gradually, nether the protection of the Regime and through the influence of skilful counsels, to cast off their vicious habits and go an interesting, civilized, and Christian customs."xiv

The experience of the Cherokee was particularly savage. Despite many tribal members adopting some Euro-American ways, including intensified agriculture, slaving, and Christianity, state and federal governments pressured the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Cherokee Nations to sign treaties and surrender country. Many of these tribal nations used the police force in hopes of protecting their lands. Virtually notable amid these efforts was the Cherokee Nation's endeavour to sue the land of Georgia.

Beginning in 1826, Georgian officials asked the federal government to negotiate with the Cherokee to secure lucrative lands. The Adams administration resisted the land's asking, simply harassment from local settlers against the Cherokee forced the Adams and Jackson administrations to begin serious negotiations with the Cherokee. Georgia grew impatient with the process of negotiation and abolished existing country agreements with the Cherokee that had guaranteed rights of movement and jurisdiction of tribal law. Andrew Jackson penned a alphabetic character soon afterwards taking role that encouraged the Cherokee, amidst others, to voluntarily relocate to the West. The discovery of gold in Georgia in the fall of 1829 farther antagonized the state of affairs.

The Cherokee dedicated themselves against Georgia's laws by citing treaties signed with the United States that guaranteed the Cherokee Nation both their land and independence. The Cherokee appealed to the Supreme Court confronting Georgia to prevent dispossession. The Court, while sympathizing with the Cherokee'due south plight, ruled that information technology lacked jurisdiction to hear the instance (Cherokee Nation five. Georgia [1831]). In an associated case, Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the Supreme Court ruled that Georgia laws did not utilize within Cherokee territory.fifteen Regardless of these rulings, the state government ignored the Supreme Court and did little to prevent conflict between settlers and the Cherokee.

Jackson wanted a solution that might preserve peace and his reputation. He sent secretary of war Lewis Cass to offer title to western lands and the promise of tribal governance in commutation for relinquishing of the Cherokee'south eastern lands. These negotiations opened a rift inside the Cherokee Nation. Cherokee leader John Ridge believed removal was inevitable and pushed for a treaty that would give the all-time terms. Others, called nationalists and led past John Ross, refused to consider removal in negotiations. The Jackson administration refused any deal that fell short of large-scale removal of the Cherokee from Georgia, thereby fueling a devastating and violent intratribal boxing between the 2 factions. Somewhen tensions grew to the signal that several treaty advocates were assassinated by members of the national faction.16

In 1835, a portion of the Cherokee Nation led past John Ridge, hoping to prevent further tribal mortality, signed the Treaty of New Echota. This treaty ceded lands in Georgia for $v million and, the signatories hoped, would limit futurity conflicts betwixt the Cherokee and white settlers. However, almost of the tribe refused to adhere to the terms, viewing the treaty as illegitimately negotiated. In response, John Ross pointed out the U.South. government's hypocrisy. "You asked us to throw off the hunter and warrior state: We did then—you asked us to form a republican regime: We did then. Adopting your ain equally our model. You asked us to cultivate the earth, and acquire the mechanic arts. We did and so. Yous asked united states of america to learn to read. We did so. You asked us to cast abroad our idols and worship your god. Nosotros did so. At present you lot need we sacrifice to you our lands. That we volition non do."17

President Martin van Buren, in 1838, decided to press the issue beyond negotiation and court rulings and used the New Echota Treaty provisions to gild the army to forcibly remove those Cherokee not obeying the treaty's cession of territory. Harsh weather, poor planning, and difficult travel compounded the tragedy of what became known as the Trail of Tears. Xvi g Cherokee embarked on the journey; only ten one thousand completed it.18 Not every instance of removal was as treacherous or demographically disastrous as the Cherokee instance. Furthermore, tribes responded in a variety of ways. Some tribes violently resisted removal. Ultimately, over sixty-one thousand Native Americans were forced west prior to the Civil War.19

The allure of manifest destiny encouraged expansion regardless of terrain or locale, and Indian removal besides took place, to a lesser caste, in northern lands. In the Sometime Northwest, Odawa and Ojibwe communities in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota resisted removal as many lived on land n of desirable farming country. Moreover, some Ojibwe and Odawa individuals purchased state independently. They formed successful alliances with missionaries to help advocate against removal, as well as with some traders and merchants who depended on trade with Native peoples. Still Indian removal occurred in the N equally well—the Blackness Hawk State of war in 1832, for instance, led to the removal of many Sauk to Kansas.xx

Despite the disaster of removal, tribal nations slowly rebuilt their cultures and in some cases even achieved prosperity in new territories. Tribal nations composite traditional cultural practices, including common land systems, with western practices including ramble governments, common schoolhouse systems, and creating an elite enslaving class.

Some Native American groups remained too powerful to remove. Start in the tardily eighteenth century, the Comanche rose to power in the Southern Plains region of what is now the southwestern The states. By quickly adapting to the horse culture starting time introduced by the Spanish, the Comanche transitioned from a foraging economic system into a mixed hunting and pastoral social club. After 1821, the new Mexican nation-country claimed the region as function of the northern Mexican frontier, but they had little control. Instead, the Comanche remained in power and controlled the economic system of the Southern Plains. A flexible political construction allowed the Comanche to dominate other Native American groups besides equally Mexican and American settlers.

In the 1830s, the Comanche launched raids into northern United mexican states, ending what had been an unprofitable simply peaceful diplomatic relationship with Mexico. At the aforementioned time, they forged new trading relationships with Anglo-American traders in Texas. Throughout this period, the Comanche and several other independent Native groups, peculiarly the Kiowa, Apache, and Navajo, engaged in thousands of violent encounters with northern Mexicans. Collectively, these encounters comprised an ongoing war during the 1830s and 1840s equally tribal nations vied for power and wealth. By the 1840s, Comanche power peaked with an empire that controlled a vast territory in the trans-Mississippi west known as Comancheria. By trading in Texas and raiding in northern Mexico, the Comanche controlled the flow of commodities, including captives, livestock, and merchandise goods. They expert a fluid system of captivity and convict trading, rather than a rigid chattel arrangement. The Comanche used captives for economic exploitation just likewise adopted captives into kinship networks. This allowed for the assimilation of diverse peoples in the region into the empire. The ongoing conflict in the region had sweeping consequences on both Mexican and American politics. The U.S.-Mexican State of war, showtime in 1846, tin be seen as a culmination of this violence.21

In the Great Basin region, Mexican independence also escalated patterns of violence. This region, on the periphery of the Spanish empire, was still integrated in the vast commercial trading network of the W. Mexican officials and Anglo-American traders entered the region with their ain regal designs. New forms of violence spread into the homelands of the Paiute and Western Shoshone. Traders, settlers, and Mormon religious refugees, aided by U.S. officials and soldiers, committed daily acts of violence and laid the groundwork for violent conquest. This expansion of the American state into the Neat Basin meant groups such as the Ute, Cheyenne, and Arapahoe had to compete over state, resources, captives, and trade relations with Anglo-Americans. Somewhen, white incursion and ongoing wars against Native Americans resulted in traumatic dispossession of land and the struggle for subsistence.

The federal government attempted more relocation of Native Americans. Policies to "civilize" Native Americans coexisted along with forced removal and served an important "Americanizing" vision of expansion that brought an e'er-increasing population under the American flag and sought to balance aggression with the uplift of paternal intendance. Thomas L. McKenney, superintendent of Indian trade from 1816 to 1822 and the Superintendent of Indian Affairs from 1824 to 1830, served equally the chief architect of the civilization policy. He asserted that Native Americans were morally and intellectually equal to whites. He sought to found a national Indian school system.

Congress rejected McKenney'south programme but instead passed the Civilisation Fund Human action in 1819. This human action offered $10,000 annually to be allocated toward societies that funded missionaries to plant schools amid Native American tribes. Even so, providing schooling for Native Americans under the auspices of the civilization program also immune the federal government to justify taking more country. Treaties, such as the 1820 Treaty of Doak's Stand fabricated with the Choctaw nation, often included land cessions as requirements for education provisions. Removal and Americanization reinforced Americans' sense of cultural authorisation.22

Afterwards removal in the 1830s, the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw began to collaborate with missionaries to build school systems of their own. Leaders hoped education would assistance ensuing generations to protect political sovereignty. In 1841, the Cherokee Nation opened a public schoolhouse arrangement that within two years included 18 schools. Past 1852, the organization expanded to xx-ane schools with a national enrollment of one,100 pupils.23 Many of the students educated in these tribally controlled schools later served their nations every bit teachers, lawyers, physicians, bureaucrats, and politicians.

III. Life and Culture in the West

The dream of creating a democratic utopia in the West ultimately rested on those who picked upwards their possessions and their families and moved west. Western settlers commonly migrated as families and settled along navigable and drinkable rivers. Settlements often coalesced around local traditions, particularly religion, carried from eastern settlements. These shared understandings encouraged a strong sense of cooperation among western settlers that forged communities on the frontier.

Earlier the Mexican War, the West for most Americans withal referred to the fertile area betwixt the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River with a slight amount of overspill beyond its banks. With soil burnout and land contest increasing in the Due east, most early on western migrants sought a greater measure of stability and self-sufficiency by engaging in small-scale farming. Boosters of these new agricultural areas along with the U.South. government encouraged perceptions of the West as a land of hard-built opportunity that promised personal and national bounty.

Women migrants bore the unique double burden of travel while also being expected to conform to restrictive gender norms. The central virtues of femininity, according to the "cult of truthful womanhood," included piety, purity, domesticity, and submissiveness. The concept of "dissever spheres" expected women to remain in the home. These values accompanied men and women as they traveled west to begin their new lives.

While many of these societal standards endured, there frequently existed an openness of frontier society that resulted in modestly more than opportunities for women. Husbands needed partners in setting up a homestead and working in the field to provide food for the family. Suitable wives were often in brusque supply, enabling some to informally negotiate more power in their households.24

Americans debated the role of regime in due west expansion. This debate centered on the proper role of the U.South. regime in paying for the internal improvements that soon became necessary to encourage and support economic development. Some saw borderland evolution every bit a cocky-driven undertaking that necessitated private risk and investment devoid of government interference. Others saw the federal regime's function as providing the infrastructural development needed to requite migrants the push toward engagement with the larger national economy. In the end, federal help proved essential for the conquest and settlement of the region.

American artist George Catlin traveled west to pigment Native Americans. In 1832 he painted Eeh-nís-kim, Crystal Stone, married woman of a Blackfoot leader. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Economic busts constantly threatened western farmers and communities. The economic system worsened after the Panic of 1819. Falling prices and depleted soil meant farmers were unable to brand their loan payments. The dream of subsistence and stability abruptly ended equally many migrants lost their land and felt the mitt of the distant market economy forcing them fifty-fifty farther west to escape debt. As a result, the federal government consistently sought to increase admission to land in the W, including efforts to lower the amount of land required for purchase. Smaller lots fabricated it easier for more than farmers to articulate land and brainstorm farming faster.25

More anything else, new roads and canals provided conduits for migration and settlement. Improvements in travel and exchange fueled economic growth in the 1820s and 1830s. Canal improvements expanded in the East, while road edifice prevailed in the W. Congress continued to allocate funds for internal improvements. Federal money pushed the National Road, begun in 1811, further west every year. Laborers needed to construct these improvements increased employment opportunities and encouraged nonfarmers to motility to the West. Wealth promised past appointment with the new economic system was difficult to reject. However, roads were expensive to build and maintain, and some Americans strongly opposed spending money on these improvements.

The use of steamboats grew quickly throughout the 1810s and into the 1820s. As h2o trade and travel grew in popularity, local, state, and federal funds helped connect rivers and streams. Hundreds of miles of new canals cutting through the eastern landscape. The most notable of these early projects was the Erie Canal. That project, completed in 1825, linked the Nifty Lakes to New York City. The profitability of the canal helped New York outpace its East Coast rivals to become the middle for commercial import and export in the U.s.a..26

Early railroads like the Baltimore and Ohio line hoped to link mid-Atlantic cities with lucrative western trade routes. Railroad boosters encouraged the rapid growth of towns and cities forth their routes. Non only did runway lines promise to move commerce faster, but the rails also encouraged the spreading of towns farther away from traditional waterway locations. Technological limitations, constant repairs, conflicts with Native Americans, and political disagreements all hampered railroading and kept canals and steamboats as integral parts of the transportation arrangement. Nonetheless, this early institution of railroads enabled a rapid expansion after the Ceremonious War.

Economic chains of interdependence stretched over hundreds of miles of land and through thousands of contracts and remittances. America's manifest destiny became wedded not only to territorial expansion but likewise to economical development.27

Iv. Texas, United mexican states and the Usa

The fence over slavery became 1 of the prime forces behind the Texas Revolution and the resulting republic's annexation to the United States. After gaining its independence from Spain in 1821, United mexican states hoped to attract new settlers to its northern areas to create a buffer between it and the powerful Comanche. New immigrants, mostly from the southern U.s.a., poured into Mexican Texas. Over the side by side twenty-five years, concerns over growing Anglo influence and possible American designs on the area produced not bad friction between Mexicans and the former Americans in the surface area. In 1829, Mexico, hoping to quell both anger and clearing, outlawed slavery and required all new immigrants to convert to Catholicism. American immigrants, eager to expand their agricultural fortunes, largely ignored these requirements. In response, Mexican authorities closed their territory to any new immigration in 1830—a prohibition ignored by Americans who often squatted on public lands.28

In 1834, an internal conflict betwixt federalists and centralists in the Mexican government led to the political ascendency of General Antonio López de Santa Anna. Santa Anna, governing as a dictator, repudiated the federalist Constitution of 1824, pursued a policy of authoritarian central control, and crushed several revolts throughout Mexico. Anglo settlers in Mexican Texas, or Texians equally they called themselves, opposed Santa Anna's centralizing policies and met in Nov. They issued a statement of purpose that emphasized their delivery to the Constitution of 1824 and alleged Texas to be a dissever state within United mexican states. After the Mexican government angrily rejected the offer, Texian leaders presently abandoned their fight for the Constitution of 1824 and alleged independence on March two, 1836.29 The Texas Revolution of 1835–1836 was a successful secessionist motility in the northern district of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas that resulted in an independent Republic of Texas.

At the Alamo and Goliad, Santa Anna crushed smaller rebel forces and massacred hundreds of Texian prisoners. The Mexican army pursued the retreating Texian ground forces deep into East Texas, spurring a mass panic and evacuation by American civilians known as the Runaway Scrape. The confident Santa Anna consistently failed to brand acceptable defensive preparations, an oversight that eventually led to a surprise attack from the outnumbered Texian regular army led by Sam Houston on April 21, 1836. The battle of San Jacinto lasted only eighteen minutes and resulted in a decisive victory for the Texians, who retaliated for previous Mexican atrocities by killing fleeing and surrendering Mexican soldiers for hours after the initial set on. Santa Anna was captured in the backwash and compelled to sign the Treaty of Velasco on May 14, 1836, by which he agreed to withdraw his army from Texas and best-selling Texas independence. Although a new Mexican government never recognized the Democracy of Texas, the Usa and several other nations gave the new country diplomatic recognition.30

Texas annexation had remained a political landmine since the Republic declared independence from Mexico in 1836. American politicians feared that adding Texas to the Matrimony would provoke a war with Mexico and reignite sectional tensions by throwing off the balance between gratuitous and slave states. However, after his expulsion from the Whig party, President John Tyler saw Texas statehood every bit the cardinal to saving his political career. In 1842, he began work on opening annexation to national debate. Harnessing public outcry over the issue, Democrat James K. Polk rose from virtual obscurity to win the presidential election of 1844. Polk and his party campaigned on promises of westward expansion, with optics toward Texas, Oregon, and California. In the concluding days of his presidency, Tyler at concluding extended an official offer to Texas on March 3, 1845. The commonwealth accepted on July 4, becoming the twenty-eighth state.

United mexican states denounced annexation every bit "an act of aggression, the most unjust which can be found recorded in the register of modern history."31 Across the anger produced by annexation, the two nations both laid claim over a narrow strip of land betwixt two rivers. United mexican states drew the southwestern edge of Texas at the Nueces River, only Texans claimed that the edge lay roughly 150 miles farther due west at the Rio Grande. Neither claim was realistic since the sparsely populated area, known as the Nueces strip, was in fact controlled by Native Americans.

In November 1845, President Polk secretly dispatched John Slidell to Mexico Urban center to purchase the Nueces strip along with big sections of New Mexico and California. The mission was an empty gesture, designed largely to pacify those in Washington who insisted on affairs earlier state of war. Predictably, officials in Mexico City refused to receive Slidell. In grooming for the causeless failure of the negotiations, Polk preemptively sent a four-thousand-human being ground forces under General Zachary Taylor to Corpus Christi, Texas, simply northeast of the Nueces River. Upon word of Slidell's brushoff in January 1846, Polk ordered Taylor to cantankerous into the disputed territory. The president hoped that this show of forcefulness would button the lands of California onto the bargaining table every bit well. Unfortunately, he desperately misread the state of affairs. Later on losing Texas, the Mexican public strongly opposed surrendering any more basis to the United States. Pop stance left the shaky government in Mexico City without room to negotiate. On April 24, Mexican cavalrymen attacked a detachment of Taylor's troops in the disputed territory just n of the Rio Grande, killing eleven U.S. soldiers.

It took two weeks for the news to attain Washington. Polk sent a message to Congress on May 11 that summed upwards the assumptions and intentions of the United States.

Instead of this, however, we accept been exerting our best efforts to propitiate her good volition. Upon the pretext that Texas, a nation as contained as herself, thought proper to unite its destinies with our own, she has affected to believe that we have severed her rightful territory, and in official proclamations and manifestoes has repeatedly threatened to make war upon the states for the purpose of reconquering Texas. In the meantime we have tried every attempt at reconciliation. The cup of forbearance had been exhausted fifty-fifty earlier the contempo information from the borderland of the Del Norte. Simply now, after reiterated menaces, Mexico has passed the boundary of the United states, has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil. She has proclaimed that hostilities have commenced, and that the two nations are now at state of war.32

The cagey Polk knew that since hostilities already existed, political dissent would exist dangerous—a vote confronting state of war became a vote against supporting American soldiers under fire. Congress passed a declaration of war on May 13. Only a few members of both parties, notably John Quincy Adams and John C. Calhoun, opposed the mensurate. Upon declaring war in 1846, Congress issued a call for 50 thou volunteer soldiers. Spurred by promises of adventure and conquest abroad, thousands of eager men flocked to assembly points across the country.33 All the same, opposition to "Mr. Polk's War" soon grew.

In the early fall of 1846, the U.S. Army invaded Mexico on multiple fronts and within a twelvemonth's fourth dimension General Winfield Scott's men took command of Mexico City. However, the city's fall did not bring an end to the state of war. Scott'southward men occupied Mexico's capital letter for over four months while the two countries negotiated. In the Us, the war had been controversial from the first. Embedded journalists sent back detailed reports from the forepart lines, and a divided press viciously debated the news. Volunteers establish that war was not as they expected. Disease killed 7 times every bit many American soldiers as combat.34 Harsh discipline, conflict within the ranks, and trigger-happy clashes with civilians led soldiers to desert in huge numbers. Peace finally came on February ii, 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

The United States gained lands that would go the hereafter states of California, Utah, and Nevada; nigh of Arizona; and parts of New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming. Mexican officials would also have to surrender their claims to Texas and recognize the Rio Grande equally its southern boundary. The United States offered $fifteen million for all of it. With American soldiers occupying their capital, Mexican leaders had no selection only to sign.

"General Scott'south entrance into United mexican states." Lithograph. 1851. Originally published in George Wilkins Kendall & Carl Nebel, The War between the United states and Mexico Illustrated, Embracing Pictorial Drawings of all the Principal Conflicts (New York: D. Appleton), 1851. Wikimedia Commons

The new American Southwest attracted a diverse group of entrepreneurs and settlers to the commercial towns of New Mexico, the fertile lands of eastern Texas, the famed aureate deposits of California, and the Rocky Mountains. This postwar migration congenital earlier paths dating back to the 1820s, when the lucrative Santa Fe trade enticed merchants to New United mexican states and generous land grants brought numerous settlers to Texas. The Gadsden Purchase of 1854 further added to American gains north of Mexico.

The U.Due south.-Mexican War had an enormous impact on both countries. The American victory helped set the U.s. on the path to condign a world ability. It elevated Zachary Taylor to the presidency and served as a training basis for many of the Ceremonious War's future commanders. Most significantly, however, Mexico lost roughly half of its territory. Yet the United States' victory was not without danger. Ralph Waldo Emerson, an outspoken critic, predicted ominously at the start of the conflict, "We will conquer Mexico, merely it will be every bit the man who swallows the arsenic which volition bring him down in plow. Mexico will poison u.s.a.."35 Indeed, the conflict over whether to extend slavery into the newly won territory pushed the nation ever closer to disunion and ceremonious war.

Five. Manifest Destiny and the Golden Blitz

California, belonging to Mexico prior to the war, was at least three arduous months' travel from the nearest American settlements. There was some thin settlement in the Sacramento Valley, and missionaries made the trip occasionally. The fertile farmland of Oregon, like the black clay lands of the Mississippi Valley, attracted more settlers than California. Dramatized stories of Native American attacks filled migrants with a sense of foreboding, although near settlers encountered no violence and oftentimes no Native Americans at all. The tiresome progress, disease, man and oxen starvation, poor trails, terrible geographic preparations, lack of guidebooks, threatening wildlife, vagaries of weather, and general defoliation were all more formidable and frequent than attacks from Native Americans. Despite the harshness of the journeying, by 1848 approximately xx thousand Americans were living west of the Rockies, with near three fourths of that number in Oregon.

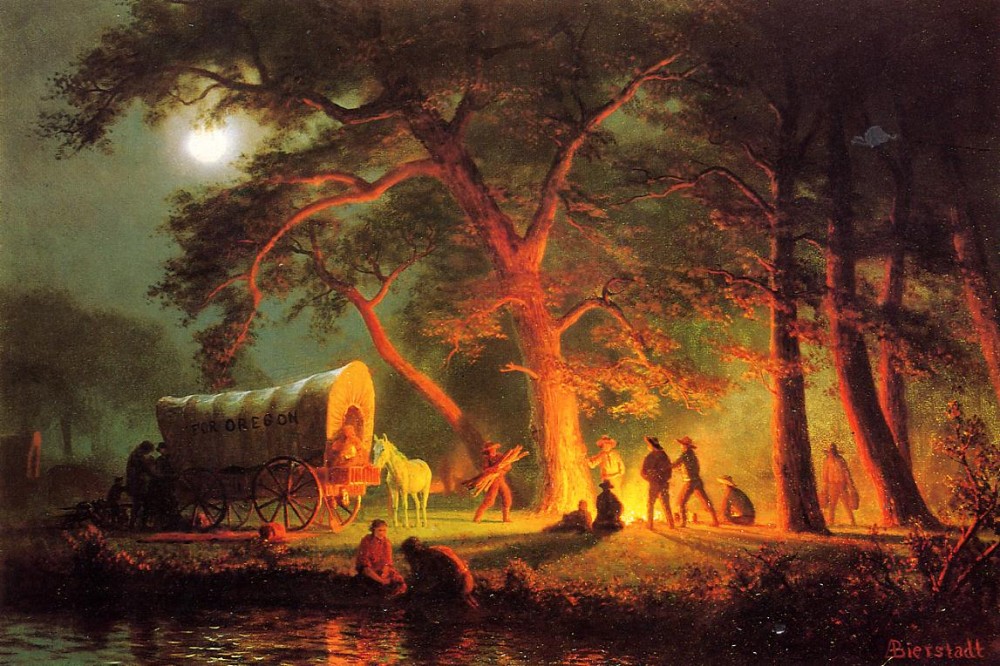

The great environmental and economic potential of the Oregon Territory led many to pack upwardly their families and head westward forth the Oregon Trail. The Trail represented the hopes of many for a amend life, represented and reinforced past images similar Bierstadt's idealistic Oregon Trail. Albert Bierstadt, Oregon Trail (Campfire), 1863. Wikimedia.

Many who moved nurtured a romantic vision of life, attracting more Americans who sought more than agronomical life and familial responsibilities. The rugged individualism and military prowess of the West, encapsulated for some by service in the Mexican state of war, drew a growing new breed west of the Sierra Nevada to meet with the Californians already at that place: a breed of migrants different from the modest agricultural communities of the well-nigh West.

If the great describe of the West served as manifest destiny's kindling, and then the discovery of gold in California was the spark that set the burn down ablaze. Nigh western settlers sought land ownership, but the lure of getting rich quick drew younger single men (with some women) to gilt towns throughout the W. These adventurers and fortune-seekers then served as magnets for the arrival of others providing services associated with the gold rush. Towns and cities grew rapidly throughout the West, notably San Francisco, whose population grew from almost five hundred in 1848 to almost 50 thousand by 1853. Lawlessness, anticipated failure of most fortune seekers, racial conflicts, and the slavery question all threatened manifest destiny's promises.

On January 24, 1848, James W. Marshall, a contractor hired by John Sutter, discovered gilded on Sutter's sawmill land in the Sacramento Valley area of the California Territory. Throughout the 1850s, Californians beseeched Congress for a transcontinental railroad to provide service for both passengers and appurtenances from the Midwest and the East Declension. The potential economic benefits for communities along proposed railroads fabricated the debate over the route rancorous. Growing dissent over the slavery issue also heightened tensions.

The cracking influx of various people clashed in a antagonistic and aggrandizing atmosphere of individualistic pursuit of fortune.36 Linguistic, cultural, economic, and racial conflict roiled both urban and rural areas. By the end of the 1850s, Chinese and Mexican immigrants made up 1 fifth of the mining population in California. The ethnic patchwork of these frontier towns belied a conspicuously divers socioeconomic arrangement that saw whites on meridian as landowners and managers, with poor whites and ethnic minorities working the mines and assorted jobs. The competition for land, resources, and riches furthered individual and collective abuses, especially against Native Americans and older Mexican communities. California's towns, besides as those dotting the mural throughout the West, such as Coeur D'Alene in Idaho and Tombstone in Arizona, struggled to balance security with economical development and the protection of civil rights and liberties.

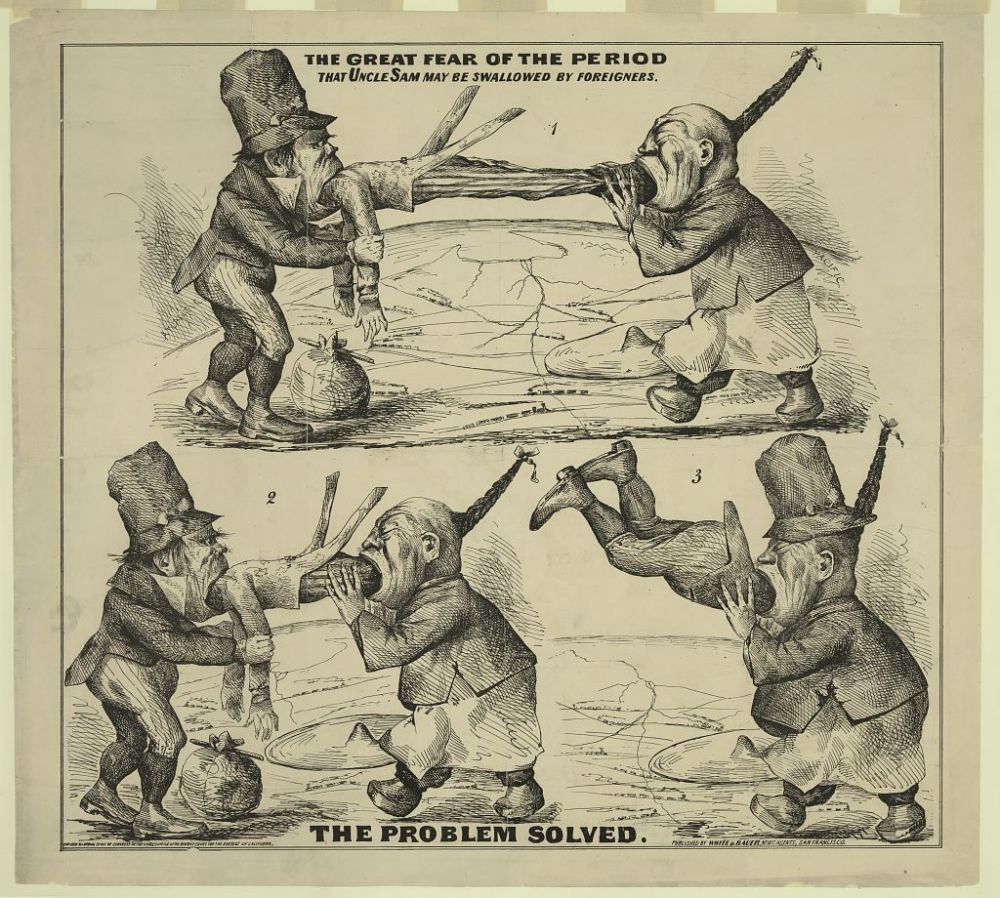

This cartoon depicts a highly racialized paradigm of a Chinese immigrant and Irish immigrant "swallowing" the Usa–in the form of Uncle Sam. Networks of railroads and the hope of American expansion tin can be seen in the groundwork. "The cracking fright of the period That Uncle Sam may be swallowed past foreigners : The problem solved," 1860-1869. Library of Congress.

VI. The Monroe Doctrine and Manifest Destiny.

The expansion of influence and territory off the continent became an important corollary to due west expansion. The U.S. government sought to keep European countries out of the Western Hemisphere and practical the principles of manifest destiny to the rest of the hemisphere. As secretary of land for President James Monroe, John Quincy Adams held the responsibility for the satisfactory resolution of ongoing edge disputes between the Us, England, Kingdom of spain, and Russia. Adams's view of American foreign policy was put into clearest exercise in the Monroe Doctrine, which he had great influence in crafting.

Increasingly aggressive incursions from Russians in the Northwest, ongoing edge disputes with the British in Canada, the remote possibility of Spanish reconquest of South America, and British abolitionism in the Caribbean all triggered an American response. In a speech before the U.South. House of Representatives on July 4, 1821, Secretarial assistant of State Adams acknowledged the American demand for a robust foreign policy that simultaneously protected and encouraged the nation'south growing and increasingly dynamic economy.

America . . . in the lapse of nigh half a century, without a unmarried exception, respected the independence of other nations while asserting and maintaining her ain. . . . She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. . . . She well knows that past in one case enlisting nether other banners than her own, were they fifty-fifty the banners of foreign independence, she would involve herself beyond the power of extrication, in all the wars of interest and intrigue, of individual avarice, envy, and appetite, which presume the colors and usurp the standard of freedom. The fundamental maxims of her policy would insensibly modify from liberty to force. The frontlet on her brows would no longer axle with the ineffable splendor of liberty and independence; but in its stead would soon be substituted an majestic diadem, flashing in false and tarnished lustre the murky radiance of dominion and ability. She might get the dictatress of the world; she would be no longer the ruler of her own spirit. . . . Her glory is not dominion, merely liberty. Her march is the march of the mind. She has a spear and a shield: merely the motto upon her shield is, Freedom, Independence, Peace. This has been her Declaration: this has been, as far as her necessary intercourse with the rest of mankind would let, her practice.37

Adams's great fright was non territorial loss. He had no doubt that Russian and British interests in North America could be arrested. Adams held no reason to antagonize the Russians with thou pronouncements, nor was he more often than not called upon to practise and then. He enjoyed a good relationship with the Russian ambassador and stewarded through Congress about-favored merchandise status for the Russians in 1824. Rather, Adams worried gravely about the power of the United states of america to compete commercially with the British in Latin America and the Caribbean area. This business organisation deepened with the valid concern that America's principal Latin American trading partner, Cuba, dangled perilously close to outstretched British claws. Cabinet debates surrounding establishment of the Monroe Doctrine and geopolitical events in the Caribbean focused attention on that part of the globe as primal to the future defense of U.S. military and commercial interests, the main threat to those interests being the British. Expansion of economic opportunity and protection from foreign pressures became the overriding goals of U.S. foreign policy.38 But despite the philosophical confidence nowadays in the Monroe administration's decree, the reality of express military ability kept the Monroe Doctrine as an aspirational assertion.

Bitter disagreements over the expansion of slavery into the new lands won from Mexico began even before the state of war concluded. Many northern businessmen and southern enslavers supported the idea of expanding slavery into the Caribbean as a useful alternative to continental expansion, since slavery already existed in these areas. Some were critical of these attempts, seeing them as evidence of a growing slave-power conspiracy. Many others supported attempts at expansion, like those previously seen in eastern Florida, fifty-fifty if these attempts were not exactly legal. Filibustering, as it was chosen, involved privately financed schemes directed at capturing and occupying strange territory without the approval of the U.S. regime.

Filibustering took greatest concur in the imagination of Americans as they looked toward Cuba. Fears of racialized revolution in Republic of cuba (every bit in Haiti and Florida earlier it) as well as the presence of an aggressive British abolitionist influence in the Caribbean energized the motility to annex Cuba and encouraged filibustering as expedient alternatives to lethargic official negotiations. Despite filibustering's seemingly cluttered planning and destabilizing repercussions, those intellectually and economically guiding the endeavour imagined a willing and receptive Cuban population and expected an amusing American business class. In Republic of cuba, manifest destiny for the first time sought territory off the continent and hoped to put a unique spin on the story of success in Mexico. However the annexation of Cuba, despite great popularity and some military attempts led by Narciso López, a Cuban dissident, never succeeded.39

Other filibustering expeditions were launched elsewhere, including ii by William Walker, a former American soldier. Walker seized portions of the Baja peninsula in Mexico and then after took power and established a slaving regime in Nicaragua. Eventually Walker was executed in Honduras.40 These missions violated the laws of the United States, merely wealthy Americans financed various filibusters, and less-wealthy adventurers were all also happy to sign up. Filibustering enjoyed its cursory popularity into the late 1850s, at which betoken slavery and concerns over secession came to the fore. By the opening of the Ceremonious State of war, most saw these attempts as simply territorial theft.

VII. Conclusion

Debates over expansion, economics, diplomacy, and manifest destiny exposed some of the weaknesses of the American arrangement. The chauvinism of policies like Native American removal, the Mexican War, and filibustering existed alongside growing anxiety. Manifest destiny attempted to brand a virtue of America's lack of history and turn it into the very basis of nationhood. To locate such origins, John O'Sullivan and other champions of manifest destiny grafted biological and territorial imperatives—common among European definitions of nationalism—onto American political civilisation. The United States was the embodiment of the democratic ideal, they said. Democracy had to be timeless, dizzying, and portable. New methods of transportation and communication, the rapidity of the railroad and the telegraph, the rising of the international market economy, and the growth of the American borderland provided shared platforms to aid Americans think beyond local identities and reaffirm a national grapheme.

Eight. Primary Sources

1. Cherokee petition protesting removal, 1836

Native Americans responded differently to the constant encroachments and attacks of American settlers. Some resisted violently. Others worked to adapt to American culture and defend themselves using particularly American weapons like lawsuits and petitions. The Cherokee did more to adapt than perhaps any other Native American grouping, creating a written constitution modeled off the American constitution and adopting American culture in dress, speech communication, religion and economic activity. In this certificate, Cherokee leaders protested the loss of their territory using a very American tactic: petitioning.

ii. John O'Sullivan declares America's manifest destiny, 1845

John Louis O'Sullivan, a popular editor and columnist, articulated the long-continuing American belief in the God-given mission of the Usa to lead the world in the transition to democracy. He called this America's "manifest destiny." This idea motivated wars of American expansion. He explained this idea in the following essay where he advocated adding Texas to the United States.

3. Diary of a woman migrating to Oregon, 1853

The experience of migrating due west into territory nevertheless controlled by Native Americans was hard and unsafe. In these diary excerpts nosotros find the feel of Amelia Stewart Knight who traveled with her husband and vii children from Iowa to Oregon. She was pregnant the entire trip and gave birth to her eighth kid on the side of the road near the journeying's end.

iv. Pun Chi Complains of racist corruption, 1860

The California Gilt Blitz of 1849 brought a major influx of Asian immigrants to the new state. This number simply grew after railroad companies turned to Chinese laborers to build western railroads. Life for these immigrants was specially hard, as even financially successful Chinese immigrants faced considerable discrimination. In 1860, the Chinese merchant Pun Chi drafted this petition to congress, calling on the legislature to do more to protect Chinese immigrants.

5. Wyandotte woman describes tensions over slavery, 1849

In 1843, the Wyandotte nation was forcefully removed from their homeland in Ohio and brought to the Kansas Territory. They found themselves on a frontier between Native American territory and Missouri's slave society, and when the national Methodist church split, debates over slavery threatened the Christianity of the Wyandotte. This letter depicts the complex relationship between recently removed Native peoples, Christianity, and slavery.

6. Letters from Venezuelan General Francisco de Miranda regarding Latin American Revolution, 1805-1806

During a trip to the The states, Venezuelan General Francisco de Miranda worked to launch a revolution in Venezuela that he expected would spread throughout Due south America. He made a series of high-level contacts, equally indicated in the letters below. The American public saw South American revolutionaries as "fellow republicans." At to the lowest degree three American ships, numerous American guns, and about 200 recruits participated in Miranda'southward failed endeavour at Revolution.

7. President Monroe outlines the Monroe Doctrine, 1823

The spirit of Manifest Destiny had its corollary in an earlier slice of American foreign policy. Americans sought to remove colonizing Europeans from the western hemisphere. As Secretary of Land for President James Monroe, John Quincy Adams crafted what came to be chosen the Monroe Doctrine. President Monroe outlined the principles of this policy in his seventh annual message to Congress, excerpted here.

8. Manifest destiny painting, 1872

Columbia, the female person figure of America, leads Americans into the West and into the future by carrying the values of republicanism (as seen through her Roman garb) and progress (shown through the inclusion of technological innovations similar the telegraph) and clearing native peoples and animals, seen being pushed into the darkness.

9. Anti-immigrant cartoon, 1860

Many white Americans responded to increasing numbers of immigrants in the 1800s with nifty fear and xenophobic hatred, seeing immigrants every bit threats to their vision of manifest destiny. This cartoon depicts a highly racialized image of a Chinese immigrant and Irish immigrant "swallowing" the United States–in the form of Uncle Sam. In the 2nd epitome, the Chinese immigrant swallows the Irish immigrant. Networks of railroads and the promise of American expansion can be seen in the groundwork.

Ix. Reference Material

This affiliate was edited by Joshua Beatty and Gregg Lightfoot, with content contributions by Ethan Bennett, Michelle Cassidy, Jonathan Grandage, Gregg Lightfoot, Jose Juan Perez Melendez, Jessica Moore, Nick Roland, Matthew K. Saionz, Rowan Steinecker, Patrick Troester, and Ben Wright.

Recommended citation: Ethan Bennett et al., "Manifest Destiny," Joshua Beatty and Gregg Lightfoot, eds., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018).

Recommended Reading

- Blackhawk, Ned. Violence over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American Due west. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

- Brooks, James F. Captives and Cousins: Slavery, Kinship, and Customs in the Southwest Borderlands. Chapel Colina: University of North Carolina Printing, 2003.

- Cusick, James Thou. The Other State of war of 1812: The Patriot War and the American Invasion of Spanish East Florida. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007.

- Filibuster, Brian. War of a Thousand Deserts: Indian Raids and the U.Southward.-Mexican State of war. New Oasis, CT: Yale University Press, 2009.

- Exley, Jo Ella Powell. Borderland Blood: The Saga of the Parker Family. Higher Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2005.

- Gómez, Laura E. Manifest Destinies: The Making of the Mexican American Race. New York: New York University Press, 2008.

- Gordon, Sarah Barringer. The Mormon Question: Polygamy and Constitutional Disharmonize in Nineteenth-Century America. Chapel Hill: University of Northward Carolina Press, 2001.

- Greenberg, Amy S. Manifest Manhood and the Antebellum American Empire. Cambridge, Britain: Cambridge Academy Press, 2005.

- Haas, Lisbeth. Conquest and Historical Identities in California, 1769–1936. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

- Hämäläinen, Pekka. The Comanche Empire. New Haven, CT: Yale Academy Press, 2008.

- Holmes, Kenneth L. Covered Wagon Women: Diaries & Letters from the Western Trails, 1840–1849. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Printing, 1995.

- Horsman, Reginald. Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Hyde, Anne F. Empires, Nations, and Families: A History of the North American W, 1800–1860. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011.

- Johnson, Susan Lee. Roaring Camp: The Social World of the California Gold Blitz. New York: Norton, 2000.

- Larson, John Lauritz. Internal Improvement: National Public Works and the Promise of Pop Government in the Early United States. Chapel Hill: Academy of North Carolina Press, 2001.

- Lazo, Rodrigo. Writing to Cuba: Filibustering and Cuban Exiles in the United States. Chapel Hill: Academy of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- May, Robert E. Manifest Destiny's Underworld: Filibustering in Antebellum America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

- Merry, Robert W. A Country of Vast Designs: James K. Polk, the Mexican War and the Conquest of the American Continent. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2009.

- Namias, June. White Captives: Gender and Ethnicity on the American Frontier. Chapel Hill: University of Northward Carolina Press, 2005.

- Perdue, Theda. "Mixed Blood" Indians: Racial Structure in the Early Due south. Athens: Academy of Georgia Press, 2005.

- Peters, Virginia Pergman. Women of the Earth Lodges: Tribal Life on the Plains. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000.

- Peterson, Dawn. Indians in the Family: Adoption and the Politics of Antebellum Expansion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017.

- Richter, Daniel K. Facing East from Indian Land: A Native History of Early America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Wilkins, David E. Hollow Justice: A History of Indigenous Claims in the United States. New Haven, CT: Yale Academy Printing, 2013.

- Yarbrough, Faye. Race and the Cherokee Nation: Sovereignty in the Nineteenth Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008

Notes

- John O'Sullivan, "Annexation," United states of america Magazine and Democratic Review 17, no. one (July–Baronial 1845), 5. [↩]

- Yonatan Eyal, The Young America Movement and the Transformation of the Democratic Party, 1828–1861 (New York: Cambridge University Printing, 2007). [↩]

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, "The Young American: A Lecture Read Before the Mercantile Library Clan, Boston, February 7, 1844." http://world wide web.emersoncentral.com/youngam.htm, accessed May 18, 2015. [↩]

- See Peter Southward. Onuf, "Imperialism and Nationalism in the Early on American Democracy," in Empire'due south Twin: U.S. Anti-imperialism from the Founding Era to the Age of Terrorism, eds. Ian Tyrell and Jay Sexton (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015), 21–xl. [↩]

- Abraham Lincoln, "Lecture on Discoveries and Inventions: Start Delivered April 6, 1858." http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/discoveries.htm, accessed May 18, 2015. [↩]

- Edmund Jefferson Danziger, Great Lakes Indian Accommodation and Resistance During the Early Reservation (Ann Arbor: Academy of Michigan Printing, 2009), eleven–xiii. [↩]

- Malcolm J. Rohrbough, Trans-Appalachian Frontier, Third Edition: People, Societies, and Institutions, 1775–1850 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008), 474–479. [↩]

- Mark Wyman, Immigrants in the Valley: Irish, Germans, and Americans in the Upper Mississippi State, 1830–1860 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2016), 128, 148–149. [↩]

- Horace Greeley, New York Tribune, 1841. Although the phrase "Get west, young man," is often attributed to Greeley, the exhortation was near likely only popularized by the newspaper editor in numerous speeches, letters, and editorials and always in the larger context of the comparable and superior health, wealth, and advantages to be had in the West. [↩]

- Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson: The Form of American Empire, 1767–1821 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977), 344–355. [↩]

- Francis Newton Thorpe, ed., The Federal and State Constitutions, Colonial Charters, and Other Organic Laws of usa, Territories, and Colonies Now or Heretofore Forming the United States of America Compiled and Edited Under the Act of Congress of June 30, 1906 (Washington, DC: U.Due south. Government Printing Office, 1909. [↩]

- Thomas Sidney Jesup, quoted in Kenneth Wiggins Porter, "Negroes and the Seminole State of war, 1835–1842," Journal of Southern History 30, no. 4 (November 1964): 427. [↩]

- "President Andrew Jackson's Message to Congress 'On Indian Removal' (1830)." http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=25&page=transcript, accessed May 26, 2015. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Tim A. Garrison, "Worcester 5. Georgia (1832)," New Georgia Encyclopedia. http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/government-politics/worcester-5-georgia-1832. [↩]

- Fay A. Yarbrough, Race and the Cherokee Nation: Sovereignty in the Nineteenth Century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 15–21. [↩]

- John Ross, quoted in Brian Hicks, Toward the Setting Sun: John Ross, the Cherokees, and the Trail of Tears (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2011), 210. [↩]

- Russell Thornton, The Cherokees: A Population History (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990), 76. [↩]

- Senate Document #512, 23 Cong., one Sess. Vol. 4, p. x. https://books.google.com/books?id=KSTlvxxCOkcC&dq=lx,000+removal+indian&source=gbs_navlinks_s. [↩]

- John P. Bowes, Land Too Good for Indians: Northern Indian Removal (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016). [↩]

- Pekka Hämäläinen, The Comanche Empire (New Oasis, CT: Yale University Press, 2008). [↩]

- Samuel J. Wells, "Federal Indian Policy: From Accommodation to Removal," in Carolyn Reeves, ed., The Choctaw Before Removal (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1985), 181–211. [↩]

- William C. Sturtevant, Handbook of Due north American Indians: History of Indian-White Relations, Vol. four (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1988), 289. [↩]

- Adrienne Caughfield, Truthful Women and Due west Expansion (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2005). [↩]

- Murray Newton Rothbard, Panic of 1819: Reactions and Policies (New York: Columbia University Printing, 1962). [↩]

- Carol Sheriff, The Artificial River: The Erie Canal and the Paradox of Progress, 1817–1862 (New York: Loma and Wang, 1996). [↩]

- For more on the applied science and transportation revolutions, come across Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (Oxford, Great britain: Oxford Academy Press, 2007). [↩]

- David Reimers, Other Immigrants: The Global Origins of the American People (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 27. [↩]

- H. P. N. Gammel, ed., The Laws of Texas, 1822–1897, Vol. 1 (Austin, TX: Gammel, 1898), 1063. https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth5872/m1/1071/. [↩]

- Randolph B. Campbell, An Empire for Slavery: The Peculiar Institution in Texas, 1821–1865 (Baton Rouge: LSU Printing, 1989). [↩]

- Quoted in The Almanac Register, or, a View of the History and Politics of the Year 1846, Volume 88 (Washington, DC: Rivington, 1847), 377. [↩]

- James K. Polk, "President Polk's Mexican War Message," quoted in The Statesmen'south Manual: The Addresses and Messages of the Presidents of the United States, Inaugural, Annual, and Special, from 1789 to 1846: With a Memoir of Each of the Presidents and a History of Their Administrations; Likewise the Constitution of the Usa, and a Selection of Important Documents and Statistical Data, Vol. ii (New York: Walker, 1847), 1489. [↩]

- Amy S. Greenberg, Manifest Manhood and the Antebellum American Empire (Cambridge, Uk: Cambridge University Printing, 2005). [↩]

- James 1000. McCaffrey, Army of Manifest Destiny: The American Soldier in the Mexican War, 1846–1848 (New York: New York University Printing, 1992), 53. [↩]

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, quoted in James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 51. [↩]

- Susan Lee Johnson, Roaring Army camp: The Social World of the California Gold Blitz (New York: Norton, 2000). [↩]

- John Quincy Adams, "Mr. Adams Oration, July 21, 1821," quoted in Niles' Weekly Register xx, (Baltimore: H. Niles, 1821), 332. [↩]

- Gretchen Murphy, Hemispheric Imaginings: The Monroe Doctrine and Narratives of U.S. Empire (Durham, NC: Knuckles University Press, 2009). [↩]

- Tom Chaffin, Fatal Glory: Narciso López and the First Hole-and-corner U.S. War Against Cuba (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1996). [↩]

- Anne F. Hyde, Empires, Nations, and Families: A History of the N American W, 1800–1860 (Lincoln: Academy of Nebraska Press, 2011), 471. [↩]

Chapter 12 Guided Reading Answers Georgia and the American Experience

Source: https://www.americanyawp.com/text/12-manifest-destiny/